by Lauren Higginbotham, Patrick Norvelle, Rebecca Schoeb, and Kaelyne Yumul

Introduction

Introduction

The premise of Henry V hinges on the war between England and France during the early 15th century. King Henry V sparked a conflict between the two countries that was rooted in a desire to gain land and authority. Tracing the sources of conflict is necessary to qualify the war in the play as a just war. Upon consideration of just war theory, the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas qualifies the war as just. While Henry V satisfied a component of divine right, his intentions were malicious and cruel. As a result, the Battle of Agincourt exemplified the death of chivalry and the consequences for not abiding by the conditions of ethical warfare.

Aquinas on Just War

The tenants of St. Thomas Aquinas’s philosophy may be incorporated as a tool for gauging the justification of war as presented in Shakespeare’s Henry V. Aquinas serves as the cornerstone for Christian Pacifism and the movement towards the ethical and just appeals for war with regards to Christians fighting in religious and political wars. Shakespeare’s understanding of moral warfare discusses the several components of the just war theory established by Aquinas. Throughout King Henry V’s search for a motivation to battle, Shakespeare undermines the practicality of the just war theory and demonstrates that divine power supersedes the intention and aim for war.

Components For Just War

To begin his political theory regarding waging a just war, Aquinas enumerates specific conditions that must be fulfilled in order for war to be considered ethical. One component relies on the right authority in order to declare war on another country. For example, King Henry V was bestowed divine right of kingship once he was crowned king. Therefore, King Henry V held the right authority in order to declare war against France. However, though King Henry V may have been legally allowed to declare war, he did not have the proper authorial context in order to justify war. The authority from the divine right of kingship derives from obedience to God (Lang). In the eyes of Aquinas, God, justice, and charity are all interchangeable. God himself would not have approved of a war against France as the intentions of King Henry V were fraudulent and malicious. King Henry V yearned to acquire the territory of France rather than to create a peaceful order. Consequently, King Henry V maintained the political authority to declare war on France, but he lacked the divine authority.

The second component of Aquinas’s theory relies on the right intentions of war. Similar to St. Augustine, Aquinas is concerned with the “virtue of justice” (Cole). However, the primary virtue Aquinas focuses on is the “infused supernatural virtue of charity” (Cole). Therefore, the entirety of his just war theory hinges on a desire to establish peace as a final destination. Aquinas notes that if the intention behind warfare is not to create peace among nations or peoples, then the war in itself is not just. The focus of a war should always “promote what is good and avoid what is evil” (Cole). Specifically noted is Aquinas’s condemnation for “the lust of power” which is strongly evident in King Henry V’s desire to gain French territory (Cole). Though King Henry V may have had the right political authority and the appearance of a right intention for engaging in battle, the war is unethical, immoral, and unjust as Henry’s “lust of power” overwhelms the aim for peace.

Just War in Henry V

The character of the Bishop of Canterbury generates the question of whether or not war against France was justified in Henry V. Canterbury references Salic law, which calls for the divine right of the king being passed down through the mother. Because of the matriarchal lineage, the Bishop of Canterbury uses the French system of authority as legal justification for the English to invade France. Salic law does not comply with the Christian emphasis on patriarchal lineage. Katherine Eggert says “most critics have found it difficult to construe this speech itself as anything but a throw away a, purely legalistic discussion that merely gives Henry the excuse to act” (Eggert 523). Most readers and critics recognize that Canterbury and Henry V use Salic Law to justify a land grab. Canterbury is also trying to protect his church grounds, so this law makes it possible for him to do so. This is a perfect example of how historical actors construct a skewed narrative in order to gain what they desire.

On the contrary, King Harry seems to be struggling with the burden of being a historical agent, which is the same pressure that his father, King Henry IV experienced. King Henry IV recalls the crown being too heavy to wear which exemplifies the significant burdens of divine authority. King Harry believes that if he is not a man of aggressive action, he will simply be forgotten by history. Consequently, he uses a disconnected and ambiguous legal reason to justify waging war against France. Ironically, in Canterbury’s speech to King Harry at the end of Act one, he says his legal reasoning is “as clear as is the summer’s sun”(1.2.86). The audience recognizes that the legal justification for invading France is not clear. Therefore, Canterbury is simply seeking his own benefit by encouraging Henry V to war with France and pursue his desire to live as a man of action.

Due to Henry V’s “lust for power,” the relationship between England and France is heavily strained (Cole). The complicated relationship between the two countries is manifested in the end of scene 1.2 when Dauphin gives tennis bells to King Harry as sarcastic “treasures.” Dauphin patronizes Harry. He views Harry as a naive and young man who is not mature enough to make substantial decisions for his country. Some critics say “the episode of the tennis balls is often pointed to as a reflection of the Dauphin’s immaturity, but he may be wiser than one normally would suspect. He correctly questions Henry’s miraculous conversion from a giddy, shallow youth to a serious monarch” (Braddy 191). Up until Harry becomes the monarch of England, no one had reason to believe that he had the ability to serve as the chivalric leader. However, Harry responds to Dauphin’s insulting actions by saying that they will “have matched our rackets to these balls/We will in France, by God’s grace, play a set” (1.2 262-262). King Harry metaphorically turns the tennis balls into cannon balls of war. Braddy argues that Shakespeare never intended for the tennis balls to make Dauphin seem immature to the reader. Holinshed’s version of Henry V does not include the tennis balls in this scene , which begs the question of why Shakespeare found it necessary to include them in his play. It can be concluded that Shakespeare intended for Dauphin to be a respectable foil for Henry V, so that Harry would be seen as “an ambitious and all-conquering English prince” (Braddy 196). Dauphin’s respectable foil compliments King Harry and presents him in a more valiant light even in the midst of the confusion of the blurred line between just and unjust war between England and France.

15th Century Tennis Ball

Political Climate

When discussing kingship and one’s right to power, war is often a topic of interest. Henry V, the second monarch of the House of Lancaster, was a ruthless king and brilliant military leader. For Henry V and the Lancaster Reign, the right to rule was from God. Shakespeare’s Henry V opens with two bishops acting more like politicians than religious leaders (Murley, Sutton 17). Henry has threatened to take the French church lands. In order to avoid the loss of land, the church supports his move against France, in hopes to keep their land – it is all manipulation and maneuvers.

Henry V truly believes he is a soldier of God and that “God [was] entirely on his side in his war against the French” (Kelly 34). The divine providence of God was on the Lancaster’s side in all things, thus giving Henry a royal prerogative to go to war. After Agincourt, he even said to the French that he was only doing God’s bidding and punishing them for their sins: “it is not we who have made this great slaughter, but the omnipotent God, and, as we believe, for a punishment of the sins of the French” (Kelly 34).

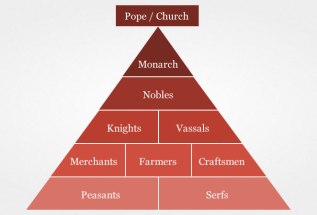

The social stratification during the reign of Henry V emphasizes the unequal distribution of power. Lancastrian constitutionalism lasted little more than half a century because of it’s power-struggle set up. This constitutional government was not destined to succeed during medieval times and circumstances because it called for a weak government. As you can see in the figure below, power was not divided equally among the mass public, but held largely and solely by landowners and monarchy. The aristocracy fought amongst themselves for more land, only causing anarchy at home. It is important, then, to note Henry’s influential St. Crispin’s Day speech. By rallying the soldiers, mainly lower-class citizens, he gave them not only support and confidence, but the power to control their own lives, deaths, and destinies, something the aristocracy and monarchy had yet to ever give them. The Battle at Agincourt left the legacy of the House of Lancaster and Henry V solely tied to the Hundred Years War and that day.

The Battle of Agincourt

On October 25, 1415, the Battle of Agincourt determined the relationship between the French and the English. Henry V waged this enormous battle in an attempt to uphold his place in history. Holinshed and Shakespeare both wrote about the Battle of Agincourt in their works: “What few commentators have realized, however, is that Holinshed does not provide just one order of events to follow, but offers two different and irreconcilable accounts that Shakespeare, and not a few of his editors, have conflated into one” (Edelman 36). The Battle of Agincourt justifies war because Henry V came out victorious; thus indicating that Henry V had the “divine right” to wage war on the French.

The Battle of Agincourt was the end of chivalry. Knights once ruled the battlefield, but technology eluded the sharp blades and armor of the chivalrous men by bringing in items such as the longbow, it was possible to elude the horse mounted noblemen. The English were shorthanded in the war, but were able to use the advanced technology combined with the rain soaked landscape to conquer their French counterparts. The French sources claimed French deaths varied between 4,000 and 10,000 casualties while England suffered minor losses of 1,600; however, the English reported that the French lost 1,500 to 11,000 while the English lost only 100 soldiers (Ann Curry 26). Discrepancies in war casualties are common throughout history.

Holinshed and Shakespeare both depict powerful speeches to demonstrate that Henry V genuinely believed in the war. Henry V expresses“the fewer men the greater share of honour. God’s will, I pray thee wish not one man more” (Henry V 4.3.24). Henry V encourages his soldiers by exclaiming “I would to God there were with Vs now so many good soldiers as are at this houre within England!…I would not wish a man more here than I have…we are indeed in comparison to the enemies but a few, but, if God of his clemencie doo favour Vs, and our just cause (as I trust he will) we shall speed well inough (Holinshed 79). Henry V uses the divine right of the king to justify his starting the war; therefore, he was justified in the end when they were victorious.

The Holinshed Chronicles display the Battle of Agincourt as a victory for the English; however, for the French the war was lost because “the king ruled by will” (Holinshed 83). Meanwhile, in England there were “solemne processions and other praisings to the almightie God with boune-fires and ioifull triumphes…..the citizens of London went to…the church…in devout manner, rendring to god hartie thanks for such fortunate lucke sent to the king and his armie” (Holinshed 82 ). Holinshed justifies King Henry V’s choice to battle because his decision to wage war demonstrates that God was on the Englishman’s side. In the eyes of the English, the French were ruled by individual will which allowed God to favor the English.

Conclusion

The just war theory is undermined by divine power in Henry V, and ultimately justifies England going to go to war with France. However, King Henry’s intentions were also malicious and lustful as he sought to gain territory in France rather than generate peaceful order. Salic law was used as a throw away excuse for Canterbury to keep his church grounds, and for King Henry V to maintain his reputation in history as a man of action. The complicated relationship between France and England is illustrated through the image of the sarcastic “treasure” of tennis balls that Dauphin gives to King Henry. Shakespeare included this image to present Dauphin as a foil to King Henry in order to illustrate him as a valiant and mature English King in the midst of the blurred line between just and unjust war. However, it is also true that divine providence was on the Lancaster’s side in all things, giving Henry the royal prerogative to go to war. This was further supported when England came out of the Battle of Agincourt victorious. In the end, the fact that King Henry’s intentions were of malicious nature played out in the battle when it resulted in the end of chivalric code, and many other consequences due to not fighting by the rules of ethical warfare.

Bibliography

Braddy, Haldeen. “Shakespeare’s Henry V and the French Nobility.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 3, No. 2 (1961) : 189-196. Web. 20 Oct. 2014.

Cole, Darrell. “Thomas Aquinas on Virtuous Warfare,” The Journal of Religious Ethics,Vol. 27, No. 1 (1999): 57-80. Web. 20 Oct. 2014

Curry, Anne (2000). “The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations.” The Boydell Press. Print.

Edelman, Charles. “‘Then Every Soldier Kill His Prisoners’: Shakespeare at the Battle of Agincourt.” Parergon 16.1 (1998): 31-45. Print.

Eggert, Katherine. “Nostalgia and the Not Yet Late Queen: Refusing Female Rule in Henry V.” ELH, Vol. 61, No. 3 (1994) : 523-550. Web. 27 Oct. 2014.

“Feudalism.” Medieval Wall. Web. 15 Nov. 2014.

Holinshed, Raphael. Henrie the Fift, Prince of Wales. 1580. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image.

Kelly, Henry Ansgar. Divine Providence in the England of Shakespeare’s Histories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1970. Print.

Lang, Anthony. Just War: Authority, Tradition, and Practice. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press 2013.

Murley, John A., and Sean D. Sutton. Perspectives on Politics in Shakespeare. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2006. Print.

Raphael, Holinshed. Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Vol. 3. Great Britain: Brooke, Printer, 1808. 80-84. Print.

“Real Tennis Balls.” Museum of London. Web. 16 Nov. 2014.

Shakespeare, William. “Henry V.” The Norton Shakespeare. 2nd ed. New York-London: W.W. Norton, 2008. 1526-1527. Print.